Ellis Bell: the heroic man and soulful choice behind Emily Brontë's pseudonym

For whom did the 3 Bells toll?

“There appears to be no clue to the origin of Emily's choice of name, Ellis” Winifred Gérin, Brontë scholar

Almost 200 years have already passed since the death of Emily Brontë, and yet the experts still haven’t figured out the inspiration behind her pen-name. Could it be that it’s because they aren’t reading the books Emily read, and through her own eyes?

In this article I will share what I have discovered about this mystery, hoping it can add to the debate. I will start with the first name, ELLIS, then the surname BELL:

What we know for sure about ELLIS

ELLIS was a male name, so we have to look for a man as the inspiration.

It is Charlotte Brontë herself, in the famous preface to a new edition of ‘Wuthering Heights’, after Emily died, who wrote: “Averse to personal publicity, we veiled our own names under those of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell; the ambiguous choice being dictated by a sort of conscientious scruple at assuming Christian names positively masculine…”1. So the names had to sound manly, but remain a bit ambiguous.

No Robert or Mark or Paul for them, but those names still had to sound manly enough…

Emily had to come up with a name starting with an E.

It is quite undisputed and easy to see that the sisters chose a pseudonym starting with their own initials: C for Charlotte (Currer Bell), A for Anne (Acton Bell), E for Emily (Ellis Bell), so Emily was restricted in her search for an inspiring manly name or hero. So the one she chose may not have been her favourite male hero, but the next best thing.

What we can speculate

Currently, to the best of my knowledge, only two lukewarm speculations for Emily’s choice of pseudonym have received any notice:

In the Brontë’s Bible (‘The Brontës’ by Julia Barker)2, Bellis is mentioned as the name of a family living in a village near Haworth. There is a whole Wikipedia page on a member of this family, Mr. Ellis Cunliffe, a politician. He was 44 years older than Emily and his wealthy family owned a few mills in the area and sometimes made the news. By the time Emily was 26, he had already taken his third wife. I doubt this was an inspiring fact in Emily’s eyes. And if he did something so heroic, masculine and memorable as to influence the serious, pondered choice of a pseudonym, we are not told. There is no record of anything particularly impressive about him. I guess the idea for this option came up after someone scoured through digital issues of local newspapers, looking for this surname. An uninspiring search in itself.

That’s not how I went about looking for my Ellis. To me the name didn’t just have to be famous locally, but be the name of a man Emily would look up to.

Despite the fact that Charlotte openly talked of ‘male names’, a woman’s surname has been suggested by a few people: Mrs Sarah Ellis, the writer of a book called ‘The Mothers of England’ and another one called ‘The Daughters of England’, where she literally tells women in the very first pages that ‘the first thing of importance is to be content to be inferior to men’ and further on she adds that a woman, ‘beyond the sphere of her affection, she has nothing and is nothing’.3 Even if the book has some redeeming qualities here and there, would Emily have gone to the trouble of choosing a man’s name, only to be tracked back to a woman, and a woman who thought women inferior?

And so it is among Emily’s favourite male heroes that I started searching…

Emily ‘s favourite male hero

As we know from Charlotte’s own words, the character of Shirley in her second eponymous novel was supposed to represent “what Emily would have been had she been born into a wealthy family, and healthy”.4 And in that novel we get to hear a clear definition of such a male hero, and even his name:

"I have been in love several times, with heroes of several nations and philosophers. My hero […] has the clearness of the deep sea, the patience of its rocks, the strength of its waves. He has been unscared by the howl and he will be unelated by the shout. Neither his title, wealth, pedigree, nor poetry avail to invest him with the power I describe. These are feather-weights: they want a ballast.”5

At that point, the uncle in the story asks Shirley if such an individual was just a description or existed somewhere: “Pray, did you paint from the life?”. And Shirley/Emily answers him: "It was an historical picture from several originals."

So her heroes were very much alive and kicking. Did she have a favourite among the men of the ‘actual present’? Shirley certainly did and she confessed it openly to us readers:

"Confess I must: my heart is full of the secret. It must be spoken. [...] I am going to tell you; his name is trembling on my tongue [...] Listen! Arthur Wellesley, Lord Wellington.”

Obviously Wellington could not be chosen as a surname by Emily Brontë. It would have been disrespectful, ridiculous, way too recognisable and conceited. Besides, it did not start with an E! But the fact that Emily (and the whole family) idolised this man is again indisputable. We know from many records, beside their juvenilia and their imaginary ‘Wellingtonsland’ etc. how fond they were of this hero, the very man who - as they wrote in their early writings - had “set Europe free from iron chain of a despot”. That was their masculine standard, no less.

So that’s why I chose to start from Wellington, hoping he would lead me to the right track, and since I am more determined than a bloodhound when I smell a trail, I did not give up until I found what I sensed was there. Luckily my patience paid off…

Following tracks down to Waterloo

I began at the beginning, by reading a biography of the Duke. Not any modern biography of the worthy man, but a few biographies and books about him which I wanted to make sure Emily Brontë may have read herself, so that I could see things through her eyes. We know that one book in particular, ‘The Life of Napoleon Buonaparte Emperor of the French’ in nine volumes by Walter Scott6, was certainly owned by the family and we are told by the experts that all the girls knew it well. Scott was also one of Emily’s favourite writers, and that biography had been published in 1827, well before Emily first had her poems printed as Ellis Bell. So I put on my Emily Brontë’s hat (and glasses) and started reading it through her eyes.

I mainly focused on the sections mentioning the Duke of Wellington, soaking up every detail of the most glorious battle of Waterloo, where he defeated Napoleon. But alas! I found no mention of any Ellis whatsoever. Someone else may have finished searching at that point, but oh no, no not me.

Something led me to want to know more of that famous battle, and that’s how I came across another book by W. Scott which contained a detailed account of the battle, and a few letters written by Wellington himself about it, a book published in 1815, right after the battle. I was luckily fooled, by chance, into thinking that this W. Scott was THE famous Walter Scott7. It wasn’t! This was only a General with the same initials. Had I known it, I may not have kept reading. But thankfully instead I persevered, until I got to the pages reporting Wellington’s own dispatch addressed to the Secretary of State, Earl Bathurst, a dispatch that Wellington wrote ten days after the famous battle, with the list of the fallen soldiers and the wounded. Despite the boredom, I guessed Emily would have been very curious to read a famous letter written by her hero himself, a letter which was certainly often quoted in newspapers and other biographies of the Duke, so I proceeded reading. It was blissfully short.

And there IT was, in Wellington’s own laudatory words: the name of ELLIS!

Orvillè, June 29th 1815

‘My Lord,

being aware of the anxiety existing in England to receive the returns of killed and wounded in the late actions, I now send lists of the officers […] Your lordship will see in the enclosed lists the names of the most valuable officers lost to his Majesty’s service. Among them I cannot avoid to mention Colonel Cameron of the 92nd and Colonel Sir H. Ellis of the 23rd Regiments, to whose conduct I have frequently drawn your Lordship’s attention, and who at last fell distinguishing themselves at the head of the brave troops that they commanded.

Notwithstanding the glory of the occasion, it is impossible not to lament such men, both on account of the public and as friends.

I have the honour to be &C.

Wellington’8

Colonel Sir Henry Walton Ellis

Imagine how I felt when I saw that not only the name Ellis was mentioned but that the Brontë’s hero himself had singled him out, out of thousands and thousands of dead soldiers and officers! Certainly if this young man who gave his life ‘to set Europe free from the iron chain of a despot’, and who ‘fell gallantly’, dying ‘pierced with honourable wounds’ (as W. Scott reports), was inspiring enough to be praised by the very illustrious Duke of Wellington himself, he could definitely merit becoming Emily’s pseudonym (at least more than the local politician with three wives and the Lady who thought women were inferior to men). But you will judge for yourselves.

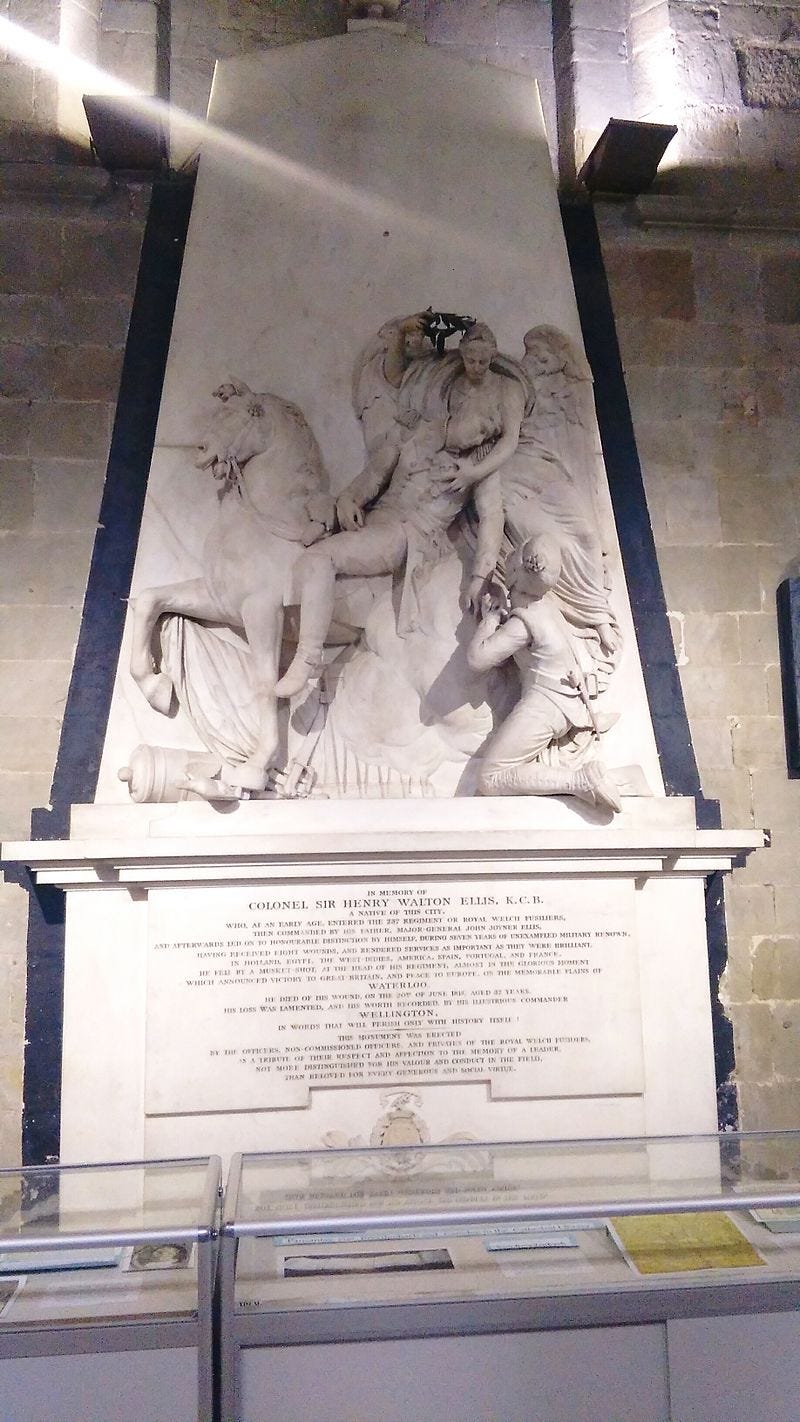

First though I will leave you with a few more details about Colonel Ellis, which I found out while researching his life and death a bit more. Inside Worcester Cathedral, you can still admire an impressive monument erected to his memory, depicting him falling from his horse during that battle, with Victory crowning him.

The writing on the monument says that he was remembered as: "…a leader not more distinguished for his valour and conduct on the field, than beloved for every generous and social virtue". We also know (and Emily likely heard it too, since she also lived in Belgium for a year as we know, not far from Waterloo) that the day before the famous battle, Ellis had marched with his troops from a small town 8 hours’ walk from Waterloo, without stopping. So it seems to me that we are in the presence of a man who was ‘unscared by the howl and unelated by the shout’, and who possessed ‘the clearness of the deep sea, the patience of its rocks, the strength of its waves’.

And finally, as an aside, the Belgian town where he began this long march under the rain was called GRAMMONT. Does that ring a bell? Well, I admit it was too tempting for me not to see the resemblance between the name of that village and the only village mentioned in 'Wuthering Heights': GIMMERTON.

But I don't want to risk taking things too far, so I'll stop here and leave you to judge for yourself.

There are other options that I can think of, which are much simpler.

ELLIS BELL, when said fast together, sounds a lot like the name ELIZABETH.

That’s the name of one of the beloved older sisters who had died as a child.

ELLIS also sounds an awful lot like ALICE, and Alice Heaton was the mother of three adorable young boys who lived at Ponden Hall, which apparently is where Emily set ‘Thrushcross Grange’.

And now, as to the surname: BELL…

The origin of the BELL surname

“You have nothing to do but to save souls;

Therefore spend and be spent in this work”

REV. WESLEY'S RULE

Why did the sisters call themselves BELL ?

So far, to the best of my knowledge, we have four main hypotheses:

1. They might have got the idea from the surname of their new father’s curate: Arthur BELL Nicholls. This is scholar Winifred Gérin’s idea, and of course such a self-evident link can’t be denied, but at that time Charlotte did not have a great opinion of Curates in general and of the man who would then become her husband. Yet, getting a new Curate called ‘BELL’ in May 1845 may have been certainly noted by them and planted a seed in their head. But only, I believe, because they already gave the word BELL a particular meaning…

2. The three sisters had been baptized in the ‘BELL Chapel’ in Thornton.

It is easy to see how this memory of their mother, and Christians as they were, may have given weight to their decision, but it lacks substance. Why ‘Bell’ of all words? I believe that this memory of that Chapel only validated their decision, but was not their main reason for their choice of the BELL surname.

3. Bell in French is the pronunciation of ‘BELLES’, meaning ‘beautiful girls’. And they knew French very well. This may have indeed added a layer of “harmless pleasure”, as Charlotte said, to their choice of pen-name. But such a shallow meaning can’t have been their main motive surely.

4. In 1845, right at the time when they were probably choosing their pen-name, thinking of publication, a new set of six BELLS was being built in London, bought with a subscription for the Haworth Church. The bells were then installed in the tower on March 1886, just a few months before the first publication of their poems. This is a “simple fact”, says Juliet Barker in her monumental book on the Brontes, but ‘a simple fact’ it was certainly not…

Why do bells ring in Churches?

If you think they do only to call people to Mass, I need to take you back to a small Victorian book on Lancashire superstitions and folk-lore, a book which I found ‘by chance’, while looking for an original Victorian recipe of Joseph’s oatcakes and which was a treasure-trove of useful information.9

This book mentions a very ancient tradition of the area: the baptising of bells.

When new bells arrived in a village, they were baptised and given names.

This ceremony was a big deal. Why?

Because bells don’t just ring to call people to Church…

According to this book:

“Bells appeared to have had an inherent power against evil spirits.”

“By the ringing of the bell, the evil spirits were kept aloof.”

Bells “chased evil spirits from persons and places”. They could also “drive away any demon that might seek to take possession of the soul of the decreased”.

And there we have it, in a nutshell: “The devils dread bells”.

After all my research on ‘Wuthering Heights’ and its potent links with Reverend Wesley’s sermons and its deeply religious hidden moral, that last line in particular couldn’t but struck a chord. (See more about my article here)

Religious Heights: Emily's Wuthering Heights was a sermon, in Rev. Wesley's style

“I’ll extract wholesome medicine from Mrs. Dean’s bitter herbs” Mr. Lockwood Have you extracted wholesome medicine from ‘Wuthering Heights’? Chances are slim, because this novel has been profoundly misunderstood for almost 200 years. Let’s face it: how many of you would have picked up this book, if it was labelled a ‘religious novel’, a literary sermon roo…

As the religious backbone of ‘Wuthering Heights’ indicates, I believe that the three BELL sisters, like powerful human bells, were in the business of chasing devils away, and save souls from Hell. As females, they were barred from becoming Ministers of the Church, like their father, or touring preaching Methodists, like Rev. John Wesley, but they could write, and write against evil they did.

Bells ringing in Wuthering Heights

How did Emily use the word ‘bell’ in the novel, I then wondered, at the light of my idea?

“Cathy rang the bell till it broke with a twang”

She was asking for help. But the bell broke. Bad omen.

“Miss Isabella came, summoned by the bell”

She is spared in the end. She escapes. She eventually listened to ‘the Bell’.

“Gimmerton chapel bells were still ringing”, says Nelly, when Cathy is recuperating from her first bout of demonic possession, healed by a loving husband, but in the same paragraph we are told that the bells couldn’t be heard at Thrushcross Grange in the summer, because of the foliage of the tree drowning that music. And when does Heathcliff show up again, after three years’ absence? In June.

Bells couldn’t save Cathy this time from the devil.

We are also told that young Cathy, when Linton is about to die in their room, rings a bell. “A sharp ringing of the bell - the only bell we have, put up on purpose for Linton”.

And who comes out of his room and says he “wouldn’t have that noise repeated”?

Heathcliff of course. “The devils dread bells”.

Soon later Linton dies. Cathy is set free at last, from one evil character. The bells worked. She is liberated from a physical, legal type of demonic possession, which had in part been caused by her excessive compassion, in part by Mrs. Dean’s ‘many dereliction of duty’ letting evil in, and of course by cruel, evil Heathcliff himself.

Finally, at the end of the book we are told young Cathy’s “voice” is “as sweet as a silver bell”. And indeed she is the Christian heroine saving Hareton from emulating Heathcliff and becoming another demon himself.

And if you think that the Brontë girls may not have thought it was their businesses to save ‘their neighbours’ from Hell, here is one final quote from Reverend Wesley on the topic: "Thou shalt in any wise rebuke thy neighbor, and not suffer sin upon him.”

“Sin is the thing we are called to reprove, or rather him that commits sin. We are to do all that in us lies to convince him of his fault, and lead him into the right way […] If we love our neighbor as ourselves, this will be our constant endeavor; to warn him of every evil way, and of every mistake which tends to evil. (Sermon 65)

And I believe that both the three Bells’ poems and their first three masterpieces sprang from such an ardent desire to fight evil.

Thank you for reading,

E.V.A.

Brontë Charlotte, ‘Biographical Notice of Ellis and Acton Bell’, in the Editor’s Preface to the New Edition of Wuthering Heights - 19 Sep. 1850

Barker Juliet, The Brontës, wild genius on the moors - Pegasus Books - 2010, p. 566

Ellis Sarah, The Daughters of England - New York. D. Appleton and Company. 1842.

Gaskell Elizabeth, ‘The life of Charlotte Brontë’, London, Smith Elder & Co. 1857

All quotations from ‘Shirley’ are from Chapter XXXI ‘Uncle and Niece’

Scott Walter, ‘The life of Napoleon Buonaparte in V volumes’ . Robert Cadell, Edinburgh 1843

General W. Scott, Battle of Waterloo. E Cox & Son, Southwark, 1815

Wellington’s dispatch to Lord Bathurst, 29th June 1815

Harland, John; Wilkinson, Thomas Turner (16 August 1867). "Lancashire Folk-lore: Illustrative of the Superstitious Beliefs and Practices, Local Customs and Usages of the People of the County Palatine". F. Warne – via Google Books.