Religious Heights: Emily's Wuthering Heights was a sermon, in Rev. Wesley's style

“I’ll extract wholesome medicine from Mrs. Dean’s bitter herbs”

Mr. Lockwood

Have you extracted wholesome medicine from ‘Wuthering Heights’?

Chances are slim, because this novel has been profoundly misunderstood for almost 200 years.

Let’s face it: how many of you would have picked up this book, if it was labelled a ‘religious novel’, a literary sermon rooted in deeply Christian morality and with evident Methodist influences, especially Wesley’s sermons?

I probably wouldn’t have.

The prevalent inclination is to think of it as a passionate or feminist romance with a rebellious female heroine, or as a dark Gothic story with sexual undertones, which undoubtedly makes it more fun and entertaining as a film and makes Emily look cooler. Even the few times that the book has been seen as religious, the whole Wesleyan framework has not been recognised, and Heathcliff and Cathy are seen as ‘spiritual rebels’ of some sorts and still glorified for their behaviour (Heathcliff spiritual, the nerve!)

But that view completely misses the book’s true essence, and Emily’s, I believe.

Of course the irony is that had readers and experts not misinterpreted it as they did, this book wouldn’t have spread, and Emily Brontë wouldn’t be celebrated as a great novelist.

But I think it’s time to give Emily more credit and face the truth…

Since diving into the religious intricacies that Emily Brontë subtly wove into this cryptic classic may get tedious, if you are not religious, I humbly suggest that each time terms like Satan and Hell appears, you interpret them based on your personal equivalent today. For example, you may envision Satan as a violent Narcissistic or a psychopath and Hell as the experience of having to live with such a person as your partner, ex partner, child, parent, boss at work, stranger etc. You get the idea. This adaptation will make this novel still incredibly relevant for contemporary readers.

Unravelling the Wesleyan connection

Who was John Wesley, what was Methodism at the time and how can we know that Emily knew this man’s works?

Mr. Wesley was a theologian and the leader of the revival movement known as Methodism, or as Charlotte Brontë herself describes him in ‘Shirley’, “John Wesley, (was) a Reformer and an Agitator…..”. Wesley wrote hundreds of very popular sermons and his brother wrote just as popular hymns. The North of England in particular was ‘buzzing with the Evangelical Revival’. Emily’s own parents met at a Wesleyan Academy for the sons of Methodists’ itinerant preachers. The father was a follower of Reverend Wesley, and he even knew the widow of Wesley’s best friend, who helped him get a job. Their spinster aunt Elizabeth - who raised all the girls after their mother’s death - was also a staunch Methodist, as was the whole Branwell family, back in Penzance, whose next-door neighbour even hosted the Reverend during one of his Cornwall preaching tours.1 Finally, Haworth’s greatest incumbent, a few decades before Patrick Brontë, had been Reverend William Grimshaw, a great friend of John Wesley.

As for books by Wesley that Emily may have read, we know for sure that the family owed a book of Wesley’s hymns, which Anne used to sing at the piano, another book with a collection of hymns for Methodists, on top of a biography of the worthy Reverend and yet another volume by Wesley (A Christian’s Library). Their mother had also ‘left among her effects’ a popular book translated from the original Latin by John Wesley (‘Imitatio Christi’ or ‘The Christian’s pattern’), a book which – incidentally – stresses the importance of writing anonymously and of living in solitude and in silence, away from “the World and all its allurements”, very much like Emily did. The book was then given to Charlotte. It is Charlotte herself who wrote on the first page: “This book was given to me in July 1826.”2

Aunt Elizabeth also famously subscribed to ‘The Methodist Magazine’ , which we know from Charlotte that the girls read as children. And it is also very likely that they owned or read Wesley’s sermons and his famous journals. Basically, these girls were surrounded by Methodism everywhere. How could it not have left a mark on their literary creations?

In fact, we already know it did, so I don’t have to press my case too hard. We know that Charlotte quoted Wesley’s hymns in a few of her novels. She also mentioned Wesley’s sermons in ‘Shirley’: “Rose and Martin alternately read a succession of sermons—John Wesley’s Sermons”.

As for Emily Brontë herself, we are told by the experts that “Wesley’s views are echoed in two of her Belgian essays”3. As for ‘Wuthering Heights’, another scholar pointed out that her portrayal of preacher Jabes Branderham, in Mr. Lockwood’s dream, could very well be a portrait of real Methodist preacher Jabez Bunting, and I agree4. Finally, another expert wrote that “the details of the final dying scene of Heathcliff can be traced back to a story told in one of Wesley’s journals”.5

Too bad these scholars stopped at these individual details and didn’t see the forest for the trees. I am here to show you the whole forest instead.

(I already showed you the wood-cutter in the article: LET ME IN):

Love thy neighbour as thyself (except if he’s Satan!)

What was at the core of Methodism? A stress on turning the words of the Bible into a way of practical living, especially the writings of the new Testament, where Jesus gave the world two new Commandments:

“Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart, and with all thy soul, and with all thy mind. This is the first and great commandment. And the second is like unto it: thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.” Matthew 22:37-40

And if there is one thing which is clear from the first page of the book is that ‘Wuthering Heights’ is the story of two neighbours.

Mr. Lockwood, who I believe acts as the readers’ guide in this novel - giving all the keys to the main characters early on in the novel - may represent Emily Brontë herself.

Just like Emily, he doesn’t like doctors, he is a ‘misanthropist’, he is not fond of social interactions but is curious about his neighbours and their stories, just like Charlotte told us Emily was. He also represents the average Christian (and reader): someone who is a bit lost on the moors, a bit naive, who needs a lantern, a guide, some visible signposts, and who we are told meditates for hours on what Mrs. Dean tells him, so as to extract ‘a wholesome medicine from her bitter story’.

Mr. Lockwood drops us the most important password in the very first line: “I have just returned from a visit to my landlord, the solitary NEIGHBOUR that I shall be troubled with.”

But this is not the next-door neighbour we tend to think of, but the Christian concept of the word. I’ll let Reverend Wesley define it: “The persons intended by "our neighbor "are, every child of man, everyone that breathes the vital air, all that have souls to be saved.” (Sermon 65)

So good Christians should love their neighbours as themselves, we are told. And instead, because of Satan’s presence in this story, we are told through Mr. Lockwood’s first dream that “every man's hand was against his neighbour”.

And what are we supposed to do if our neighbour is evil, a Satan incarnate?

Turn the other cheek, like Hareton, and imitate him? Marry him, hoping to reform him, like Isabella? Play cards and drink with him, like Hindley? Get his wage, serve him and turn a blind eye on what he does, like Joseph? Threaten him like a bull, only to then meekly obey him and open gates for him, like Nelly? Feel sorry for him and become his best friend, like Catherine? Show up at his place uninvited, like Mr. Lockwood? Have sex with him if he’s hot?

Before I give you Emily’s and Rev. Wesley’s answer (here and in the next article), let us look at the obvious Satan incarnate of the novel…

HEATHCLIFF: the demonic heathen at Wuthering… Hell

“Next to the love of God, there is nothing which Satan so cordially abhors as the love of our neighbor. He uses, therefore, every possible means to prevent or destroy this”. Wesley (Sermon 72)

Emily tried really hard to fill us with clues showing what this evil character exemplified in the story.

And it is incredible, shocking and disappointing to see the power of romantic book-covers, and Hollywood films, in turning this devilish monster, capable of hanging a dog, beating his wife, terrorizing his niece and letting his own son die, into the hero of a romance that many women hope to find in real life and be passionately loved by, in the foolish hope of redeeming him.

Emily was clearly aware of this risk (after all Satan is defined as ‘the tempter’) which is why she has Heathcliff himself warn such foolish female readers from turning him into “a hero of romance”:

"(Isabella) abandoned (her family) under a delusion…. picturing in me a hero of romance, and expecting unlimited indulgences from my chivalrous devotion. I can hardly regard her in the light of a rational creature, so obstinately has she persisted in forming a fabulous notion of my character, and acting on the false impressions she cherished. […] (her) senseless incapability of discerning that I was in earnest when I gave her my opinion of her infatuation and herself. It was a marvellous effort of perspicacity to discover that I did not love her.”

I mean, what more was Emily supposed to write to warn us?

But if just like Isabella you too are not convinced that Heathcliff is Satan incarnate in the story, here is a list of infernal symbols associated with him and his dwelling, together with quotes from the Wesley’s sermons which I believe influenced Emily in creating this evil character. I’ve read most of them, so you don’t have to:

To begin with, he is called the devil numerous times throughout the book and uses the word plenty of time himself. Just to give you a short selection:

“What the devil is the matter?”

“Your childish outcry has sent sleep to the devil for me”

He was “dark almost as if it came from the devil”

“The Devils's carried off his soul” Joseph says at the end, when Heathcliff is dead.

Big roaring fires are burning bright and hot everywhere in Wuthering Heights. Yet, everything else in the house is pretty shabby or empty. “There is nothing beautiful in those dark abodes; no light but that of livid flames.” (Sermon 73)

Isabella, who married this monster and therefore ‘knows him carnally’, says that she would “far rather be condemned to a perpetual dwelling in the infernal regions than, even for one night abide beneath the roof of W.H. again” (notice how she doesn’t say ‘for one day’. What happened at night with Heathcliff, we are left wondering?)

Heathcliff clearly possesses “the evil eye”, which all over the world was associated with the power of harming someone through a sheer evil look. We are told that Heathcliff’s look has the power to stop and terrify people:

“Heathcliff glanced at me a glance that kept me from interfering.” says Nelly.The first time someone appears, to answer Mr. Lockwood, it is Hareton, described as“a young man without coat, and shouldering a pitchfork”. The trident is one of the oldest symbols associated with the Devil, from the middle ages. With it, it grabs souls away from God.

He brings a grouse to Lockwood and we know that “it was common to sacrifice a rooster to the devil” and “offering fowl to evil spirits” in the north of England.

He plays cards with Hindley and “the Devil’s partiality for playing at cards has long been proverbial” in those parts of the country. As Joseph also says, the Devil “always makes a third, in such ill company”

He is called black, and dirty, and dark like ‘whinstone’ (a black stone) and back then black was considered the colour of the ‘Prince of darkness’.

As an adult, he is described as an attractive ‘gentleman’. “He is a dark-skinned gypsy in aspect, in dress and manners a gentleman”, Nelly says. And, as Shakespeare says in ‘King Lear’ (the only Shakespearean text Emily mentions in the novel) “the Prince of Darkness is a gentleman”.

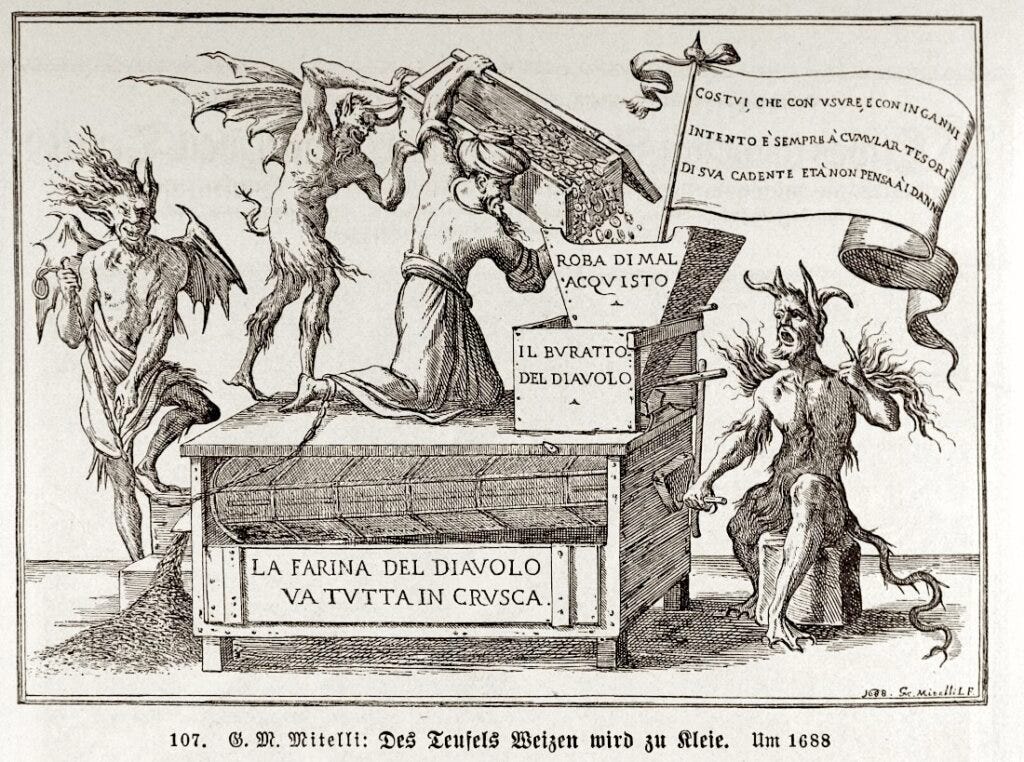

In Chapter 24, Cathy and Linton want to play together. “He consented to play at ball with me. We found two in a cupboard… One was marked C., and the other H.; I wished to have the C., because that stood for Catherine, and the H. might be for Heathcliff, his name; but the bran came out of H., and Linton didn't like it.” Why was this detail so important to mention it? I double checked. An old Italian saying, which was known in English too, was: “La farina del diavolo va tutta in crusca” - “The Devil’s flour all turns to bran”. It meant that what the Devil does, always ends badly or sour. The bran coming out of that ball is yet another sign of the devil.

He owns wild dogs. The banal thing to say is that these dogs represent “the savage, wild nature of Heathcliff”, his passionate side. But the repetition of the word ‘wild beasts’ in the book reminded me of Rev. Wesley’s sermons, letters and journals, where he constantly calls “wild beasts” all the ‘heathens’ who attacked him and other Methodists everywhere in England. Here are only some examples:

“As I began to preach, the wild beasts began roaring, stamping, ringing the bells…”6

“I was reasoning with the wild beasts…”Hindley is also described as a ‘wild beast’. And his son Hareton is terrified of encountering “his wild beast’s fondness’.

The very first description of the living room in Wuthering Heights mentions a lot of ‘pewter dishes’ on the racks. A casual remark? No word is casual with a genius like Emily. As Jane Austen told us in her letters, ‘pewter’ was another word for ‘money’ back then. We know that Heathcliff “has nobody knows what money, and every year it increases ”. Why did Emily have to specify that it’s ‘increasing’?

Rev. Wesley indicates that being rich is dangerous enough for a Christian, “but if the danger of barely having (riches) is so great, how much greater is the danger of increasing them!” Therefore, nothing can be more prudent than this caution: "If riches increase, set not thine heart upon them." (Sermon 126) We are also told know that he grows more and more avaricious, and that he “covets his neighbour’s goods” (and his wife into the bargain). Another word for the Devil is Mammon, which in Hebrew means money. This reminded me that Emily’s mother had written an article called ‘The advantages of poverty in religious concerns’, certainly a treasured possession.7

He doesn’t go to Church, he curses/swears and ‘he strives to instil atheism’ in Hareton - (sermon 72) In hell, there is no music but that of … curses and blasphemies against God (Sermon 73)

He ‘groans’ quite a lot and gnashes and grinds his teeth. As Nelly says:“I'd rather have seen him gnash his teeth than smile so”. Again Wesley wrote that: “In hell, there is no music but that of […] groans and shrieks; of weeping, wailing, and gnashing of teeth”.

Heathcliff drinks wine and offers it to his guests. Mr. Linton offers him tea instead. We know that Wesley didn’t drink wine and warned against the dangers of alcohol abuse in his sermons, wine in particular: “You see the wine when it sparkles in the cup, and are going to drink of it. I tell you there is poison in it! And, therefore, beg you to throw it away". (Sermon 140).

He is violent with animals. This is always a red flag with the Brontës, as it should be. He hangs a dog, he is a hunter, he kills birds and there are hams in full sight at Wuthering Heights. And we know Wesley was a vegetarian. “Thanks be to God, since the time I gave up flesh meals and wine I have been delivered from all physical ills”.

Just like Satan, Heathcliff likes to “torment who he cannot destroy” (sermon 42), like he torments Mr. Linton and his daughter Cathy. “If he cannot prevail upon us to do evil, he will, if possible, prevent our doing good... lessen, if not destroy, that love, joy, peace, -- that long-suffering, gentleness, goodness, -- that fidelity, meekness, temperance, -- which our Lord works by his loving Spirit in them that believe (Sermon 72)

Heathcliff also “strives to instil unbelief, atheism, ill-will…. opposite to faith and love” (sermon 72), as he does with Hareton, who grows up hating the Curate, his father and Nelly.

As for his behaviour with Isabella, before marrying her, he also“labors to awaken evil passions or tempers.... He endeavors to inspire those passions and tempers which are directly opposite to ‘the fruit of the Spirit’. That’s why he has ‘the impudence’ of embracing her (and in French, with Emily knew, this verb means ‘to kiss’) and whispers who knows what at her ears, making her turn away. “Endeavoring thus, by means of the body, to disturb or sully the soul. He is emphatically called the tempter.” (Sermon 72). As for his behaviour to her after the wedding, we all know what he did.

Just like Bluebeard, another evil character in fairy-tales, he keeps his room well locked and even his bride cannot open it.

Heathcliff is never tired. Just like ‘evil angels’ described by Rev. Wesley, he is “indefatigable in (his) bad work… never faint or weary”. “To effect these ends, he is continually laboring, with all his skill and power, to infuse evil thoughts of every kind into the hearts of men.” (Sermon 72 )

Just like Satan, “he is continually watching over children to see whose circumstances … may lay them open to temptation [… ]” and it is uncanny how he always seems to know when young Cathy is around on the moors. (Sermon 72)

Ok. I think that will suffice…

CATHERINE: A lost soul, torn between Heaven and Hell

Catherine is described from the start, in Lockwood’s nightmare, as someone who “has lost her way on the moors”. She is therefore quite literally a lost soul. Unfortunately Hollywood decided to portray her mainly as Heathcliff’s lover, but in the novel she is also clearly portrayed as very much in love with her husband, Mr. Linton.

In fact, she is literally TORN between Heathcliff and Linton.

When Catherine is categorically asked to choose between one or the other, she goes nuts and refuses to do it. “Will you give up Heathcliff hereafter, or will you give up me? It is impossible for you to be my friend and his at the same time; and I absolutely require to know which you choose” asks her Mr. Linton, after a terrible fight with Heathcliff.

And what is this, if not a symbolic rendering of her soul torn in two, between the Devil and Christ?

When as a little girl she is bitten by a dog, while spying on the children at Thrushcross grange, we are told by Heathcliff that:“The devil had seized her ankle”.

Well, we should have listened. He didn’t mean the dog. Heathcliff always means what he says, unlike Nelly, who is full of good intentions but does not act upon them (see my article: Unveiling Nelly Dean.)

Like most readers, I had never thought twice about the potential symbolism behind that ankle problem, until I read this sermon: “There is no doubt but (the Devil) is the occasion, directly or indirectly, of many of the pains of mankind, which those who can no otherwise account for them lightly pass over as nervous. And innumerable accidents, as they are called, are undoubtedly owing to his agency; such as… the breaking or dislocating of bones...” (Sermon 73)

Catherine is very much in the grip of the Devil, on and off, in the novel.

She also has bouts of lunacy and back in the Brontës’ time, and especially in the North of England, a lot of mental illness was ascribed to the Devil.

In one of his sermons, Wesley himself asks:

“Some lunatics are really demoniacs?”

“Yes”, he answers. “There is little reason to doubt but many diseases likewise, both of the acute and chronical kind, are either occasioned or increased by diabolical agency; particularly those that begin in an instant, without any discernible cause” (Sermon 72)

He then goes on to explain how even a Doctor had backed him up in his conclusion: “Many years ago I was asking an experienced physician, and one particularly eminent for curing lunacy, "Sir, have you not seen reason to believe that some lunatics are really demoniacs?" He answered, "Sir, I have been often inclined to think that most lunatics are demoniacs.”

According to a Victorian book about Lancashire folklore and superstitions8 (and let’s not forget that Emily and Charlotte went to school at Cowan Bridge, in Lancashire), the symptoms of these demoniacal distresses included:

* wild ravings

* irregular convulsions of the body

* dismal malady of the mind

* terribly fits of paroxysms to the amazement of the spectators

* sorest madness

And isn’t that the description of Catherine’s crises to a T?

Most of those words are used by Emily in the novel. Cathy says: “My late anguish was swallowed in a PAROXYSM of despair. I cannot say why I felt so wildly wretched: it must have been temporary derangement, for there is scarcely cause”

And then Nelly says: “She said nothing further till the PAROXYSM was over”

We are told in the Lancashire book how amazed spectators were at these demonic possessions, and Nelly says: “I shall never forget what a scene she acted, when we reached her chamber: it terrified me”. As for the word RAVINGS, it is again used many times by Nelly here.

Emily was trying really hard to make us ‘get the hint’.

And if we had missed the point, it is Heathcliff himself who reveals it, by asking her: “Are you possessed with a devil to talk in that manner to me, while you are dying?”

Yep. She is, indeed! And the irony of course is that she’s possessed by him (just like a woman today under the spell of a destructive partner they can’t leave).

And where did such women go, when they died, according to Emily and Wesley?

We are told by Nelly that Catherine died ‘quiet as a lamb” but Catherine certainly can’t go to Heaven, possessed by the Devil as she was, and with such a ‘wicked little soul’. She knows it herself: “Heaven didn’t seem to be my home”.

Yet she doesn’t deserve Hell either, cause she’s not fully evil.

Remember how she fasts for a few days, and recover sanity after her bouts of ‘lunacy’?

And what was fasting, symbolically, at the time?

We know that John Wesley ‘practiced a weekly fast from sundown on Thursday to sundown on Friday’ and that ‘he advocated fasting as a regular spiritual discipline’. In fact, he wrote a whole sermon on fasting and that sermon begins by saying: “It has always been the endeavour of Satan to put asunder what God has joined together” (Sermon 27). And isn’t that what Heathcliff is trying to do, breaking the sacred marriage of Linton and Catherine?

But back to Catherine’s fasting. Rev. Wesley, quoting from ‘the Homily on Fasting’, said: “When men feel in themselves the heavy burden of sin, see damnation to be the reward of it, and behold... the horror of hell, they tremble, they quake, and are inwardly touched with sorrowfulness of heart… that all desire of meat and drink is laid apart [...] (and they) show themselves weary of life.”

Wesley also reminded his readers (and Emily certainly took notice) that “Men who are under strong emotions of mind, who are affected with any vehement passion, such as sorrow or fear, are often swallowed up therein, and even forget to eat their bread. At such seasons they have little regard for food, not even what is needful to sustain nature. […] Here, then, is the natural ground of fasting…”

So Catherine was probably struggling against Satan, while fasting. And if that last quote reminded you too of Heathcliff fasting, at the end of the book, you might also remember however that he does not repent, when offered to do so and that he also refuses Nelly’s invitation to receive a Minister and read the Bible. So his fasting alone is not saving him. Wesley makes it very clear:“with fasting let us always join fervent prayer, pouring out our whole souls before God”, and adds: “in order to our standing before God in glory [...] nothing is indispensably required, but repentance, or conviction of sin.” Heathcliff does not repent at all instead. In fact, Emily clearly has Heathcliff say:

“As to repenting of my injustices, I’ve done no injustice”

(The nerve!!)

“and I repent of nothing”.

(Typical psychopath).

Besides, whereas Wesley says that in those moments of fasting and repenting, the person sees ‘the holy Ghost’, we are told that Heathcliff sees Cathy’s ghost instead!

So, since Heathcliff is clearly going to Hell (or as he calls it, ‘MY heaven’) what option is left for Catherine, in her ‘in-between state’, but... Purgatory?

The Anglican Church openly rejected Purgatory as a ‘Papist’ (Catholic) invention.

But Wesley wasn’t so clear on the subject. He believed, without a doubt, that “we must be fully cleansed from all sin, before we can enter into glory”, but he stated that not everyone agreed on the timing of that ‘cleansing’.

“Some believe it is attained before death: some, in the article of death: some, in an after-state”, he says. He also believed that there were “intermediate states, and that it is our duty to pray for those who are there.”

What did Emily believe?

Emily does use the word ‘Purgatory’ twice in the novel.

And, interestingly, the first time is about Catherine herself: “She was in purgatory throughout the day”, we are told. The second time, it is used by the victim of the devil who actually manages to escape her risk of ending in Purgatory: Isabella.

As she finally finds the courage to leave Wuthering Hell and her demonic husband behind, she says: “blessed as a soul escaped from purgatory, I bounded… precipitating myself – in fact - towards the beacon light of the Grange”.

When Catherine dies, Nelly keeps repeating how angelic she looks, how at peace she seems. Are we to trust her? Then she adds: “one might have doubted whether she merited a haven of peace at last. One might doubt in seasons of cold reflection, but not then”.

Yes Nelly. One MIGHT indeed doubt…

“Retracing the course of Catherine Linton, I fear we have no right to think she is”, she adds.

Exactly.

The idea that Catherine is going to Purgatory would also explains why we see her as a ‘ghost’ who haunts Heathcliff for years, in Mr. Lockwood’s famous symbolic nightmare. She’s not at peace. But one day she will.

Mr. LINTON: the true Christian carrying the cross and deserving heaven

If Heathcliff is a devil, and Cathy is torn between him and her husband, and if this husband is Heathcliff’s worst enemy, clearly the husband has to be the exemplification of a true Christian, or a good angel.

As Charlotte Brontë herself wrote in her famous preface, Mr. Linton is an example of real ‘CONSTANCY and TENDERNESS’.

Mr. Linton in the novel is also described as a ‘lamb’, and a ‘dove’, both symbols of Christ, and as having ‘angel’s eyes’. He is also likened to a gentle honeysuckle, while Catherine is ‘a thorn’. He’s ‘a kind Master’, trustful, honourable, devoted and patient. He is also the one carrying the cross, in the story. And Methodists lay a lot of emphasis on carrying our cross, as Jesus did. Wesley himself often mentioned the importance of “bearing our own crosses.” The Gospel says: “Those who don’t pick up their crosses and follow me aren’t worthy of me” and Wesley wrote: “Crosses are so frequent, that whoever takes advantage of them, will soon be a great gainer. Great crosses are occasions of great improvement”9

Yes, and he lives at ‘ThrushCROSS Grange’.

(I’ll cover the THRUSH symbolism in another article)

Mr. Linton was also an exemplification of ‘tenderness’, Charlotte wrote, and she said that her sister Emily strongly believed that men could be just as tender as women. And Linton’s devotion and tenderness to Catherine is certainly something to behold. Even if modern readers have been fooled by Hollywood’s portrayal of Cathy & Heathcliff’s so-called ‘romance’, the real example of true love in the book is Linton’s: both earthly love and Christian love.

“What is love?” Reverend Wesley asked his congregation in one of his sermons: “As to the measure of this love, our Lord hath clearly told us: "Thou shalt love the Lord thy God with all thy heart." Unlike Heathcliff, Edgar Linton is often described as coming or going from the Church, or rather, ‘the chapel’. As Zillah tells us, that is how Methodists used to call their meeting places. Quoting the Bible, Wesley also says that “Love is patient and kind, does not boast, is not arrogant or rude, is not irritable. He bears all things, believes in all things, endures all things.’

Again, isn’t that Mr. Linton?

In his sermon ‘The Catholic spirit’, Wesley also writes that the love we should feel for our neighbours is: “always willing to think the best / to think no evil of (one)/ (a love) that hopes… that either the thing related was never done, or not done with such circumstances as are related, or at least that it was done with a good intention”

Remember how Linton reacts when he is told that his sister Isabella ran away with Heathcliff? “This is not true! It cannot be!” he says. Ah. Bless him. Sure, he then seems to leave her alone with this evil man without lifting a finger to help, as Heathcliff himself points out, but as Isabella reminds him: “He does not know what I suffer. I haven’t written him THAT!” - The same goes when Catherine is locked in her room and ill. Nelly does NOT tell him what she is going through. He is often fooled or left in the dark.

Wesley also says: "Love suffereth long," or is long suffering. If thou love thy neighbor for God's sake, thou wilt bear long with his infirmities”. Linton certainly puts up with Catherine’s suffering, bouts of lunacy and verbal abuse with great patience and certainly puts up with Heathcliff until too much is too much, and he has to put an end to things.

After Catherine dies, Linton is also a model of proper grieving, unlike Heathcliff, who takes his grief too far. In his sermon on mourning, Wesley warns against “the unprofitable and bad consequences, the sinful nature, of profuse sorrowing for the dead.” He says we should ‘strive against it’, because “grief, in general, is the parent of so much evil, and the occasion of so little good to mankind”. (Sermon 135)

Clearly Heathcliff didn’t get the memo!

When Catherine dies, we are told by Isabella that he locked himself in his room and “there he has continued, praying like a Methodist: only the deity he implored is senseless dust and ashes; and God, when addressed, was curiously confounded with his own black father!”

Finally, Mr. Linton becomes a wonderful father to Cathy. But more on heroine Cathy and her love for ‘the Father’ (yes, the one in Heaven) in another article.

Cathy & Heathcliff: great love story or evil idolatry?

“Nelly, my greatest thought in living is Heathcliff… He is in my soul” says Catherine.

And we swoon. “Oh, how romantic. How passionate. If only I could love or be loved like that!” - Bad mistake!

That is not how Emily wanted us to look at this romance, at all!

We are told more than once in the novel that Catherine was Heathcliff’s IDOL.

And “what are the idols of which the Apostle speaks?”, asks Wesley. “The first species of this idolatry is what St. John terms, the desire of the flesh”, he answers. Enough said.

I’m not the first one who saw their love as idolatry, but without seeing this aspect inside the Wesleyan framework, this can cause people to reach the most far-fetched conclusions, even seeing that idolatry as a good thing! Or seeing Heathcliff and Catherine as “a couple of revivalists”, creators of a new sort of spirituality.10

Oh my goodness. A man who lets his own son die, hangs a dog and does what he does to his wife, called ‘spiritual’? Can someone really believe Emily was so diabolic?

I need my smelling salts…

Wesley in his sermon goes on in more depth about the sin of “idolizing a human creature”. “Undoubtedly it is the will of God that we should all love one another… but unfortunately many people end up “loving the creature more than the Creator […] It cannot be denied, that (man and wife) ought to love one another tenderly […] But they are neither commanded nor permitted to love one another idolatrously. Yet how common is this!” (Sermon 78)

Now let’s go back to the first new Commandment: Christians should love God “WITH ALL (their) SOUL, MIND and HEART”.

Now, consider Catherine’s love for Heathcliff. How does she love him?

Let me count the unChristian ways.

Catherine says:“Nelly, my greatest thought in living is Heathcliff. He is always, always in my mind” / “He’s in my soul”

Read that through Emily’s eyes now:

“Nelly, I do NOT love God with all my mind and all my soul”

Heathcliff similarly declares about Catherine: “I cannot live without my soul.”

Read that as: “I do NOT love God with all my soul.”

So in Emily’s eyes, Heathcliff is no romantic (or religious) “hero” at all. And Cathy & Heathcliff’s ‘love story’ is the sinful story of idolizing humans more than God.

Or for those who don’t believe in God, it is the danger of loving someone to the point of losing yourself or becoming obsessed with them. I’ll describe in a final article a better example of redeeming love, in the true heroine of this book: young Cathy.

Emily’s sister Charlotte, in the 1850 preface to W.H., clearly said that Catherine was ‘in the midst of PERVERTED PASSION and PASSIONATE PERVERSITY’.

That sums her up! As for Heathcliff, Charlotte tells us that 'he stands UNREDEEMED', a religious term meaning that he will go to hell, that he will not be saved, “never once swerving in his arrow-straight course to perdition”. And if you believe that his ‘redeeming grace was his love for Cathy, Charlotte is quick to put that idea to rest by saying it wasn’t, that this love was ‘a sentiment fierce and inhuman, a passion such as might boil and glow in the bad essence of some evil genius, a fire that might form the tormented centre of - the ever-suffering soul of a magnate of the infernal world… which dooms him to carry Hell with him wherever he wonders.”

In conclusion, I wonder what Emily would feel today, seeing her ‘sermon’ so misunderstood. Especially if you consider that she did not just write a book for fun, risking her precious anonymity just to let her imagination run loose.

This woman was in the business of saving souls from Hell.

She was a heroic BELL after all…

But more on the meaning of her pseudonym in another article.

Hell or no hell, God or no God, I have extracted my medicine from Emily’s bitter sermon. I hope you did too.

Thank you Emily.

And thank you for reading.

Wright Sharon, The Mother of the Brontes: when Maria met Patrick, 2019, Pen & Sword History

Clement K. Shorter, ‘Patrick Bronte and Maria, his wife’, in ‘Charlotte Bronte and her circle’, 1896

https://www.thebrontes.net/reading/w

Stuchiner, J. (2020). Wuthering Heights: Brontë’s Parable of the Unforgiving Servant. Religion and the Arts, 24(1-2), 65-83. (I have only read the abstract. I don’t say agree with everything else therefore. Only the bit about the link between Jabez and Jabes)

Sorensen, Katherine M. From Religious Ecstasy to Romantic Fulfillment: John Wesley’s Journal and the Death of Heathcliff in Wuthering Heights.Victorian Newsletter. 82 (Fall 1992)

https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=hvd.32044081153538&view=1up&seq=125&q1=gypsies

Clement K. Shorter, ‘Patrick Bronte and Maria, his wife’, in ‘Charlotte Bronte and her circle’, 1896

Harland, John; Wilkinson, Thomas Turner "Lancashire Folk-lore: Illustrative of the Superstitious Beliefs and Practices, Local Customs and Usages of the People of the County Palatine". F. Warne 1867

Wesley, John ‘Renew my heart’

Marie S. Heneghan, The Post-Romantic Way to God: Personal Agency and SelfWorship in Wuthering Heights. Australasian Journal of Victorian Studies 22.1 (2018)