“LET ME IN!” - The Aesop's fable at the core of Wuthering Heights

Unlock the 'unpalatable moral' hidden in Emily Brontë's novel

“Let me in!”

are three of the most haunting words in English literature.

Even someone who has never opened a book since secondary school will recognise them.

There are nine words actually, not three, because this famous cry is repeated three times in the third chapter of Wuthering Heights: “Let me in, let me in” sobs a ‘most melancholy voice’. And then, after a few lines, the voice still wails: “Let me in!” for a third time.

And doesn’t it sound like… an incantation?

These three magic words, repeated three times, could indeed be a secret code that Emily Brontë hid early on in the book to help us unlock the powerful moral of her masterpiece.

But before I get to the code, let me address those of you who may be understandably skeptical: “Why are you so sure that Emily HID a moral in the story? Couldn’t she have made it obvious to every reader? And couldn’t it be that she just had fun writing a Gothic tale, letting her imagination loose, without the need to impart any moral lesson whatsoever?”

‘Much soft nonsense’ Wuthering Heights is not

Well. First of all, Emily is a writer of fiction and the golden-rule in that world is: “Show, don’t tell”. If she had wanted to teach us her moral straight, she would have written an essay.

With a novel, she had to weave her moral into the plot instead, so that it could act more powerfully, like a spell. (And judging by the fact that we’re still here talking about this book, after almost 200 years, I’d say her spell worked!)

So what is this powerful hidden moral? Unfortunately we don’t have Emily’s words on this topic (we basically don’t have her words on anything, for that matter), but we have her sister’s: Anne Brontë, a sister who someone very close to them described as Emily’s “twin”, and this is what Anne says in the preface of her second novel ‘The Tenant of Wildfell Hall’:

“My object in writing the following pages was not simply to amuse the Reader, neither was it to gratify my own taste, nor yet to ingratiate myself with the Press and the Public: I wished to tell the truth, for truth always conveys its own moral to those who are able to receive it. But as the priceless treasure too frequently hides at the bottom of a well, it needs some courage to dive for it…”

Ah, dear, dear Anne. The most underestimated of the three sisters.

So, quoting from that preface again, we know that Emily’s sister believed that:

1. Novels are a way to “whisper a few wholesome truths”, rather than “much soft nonsense” 2. Jewels are often hidden in “mud and water”. (And there is certainly a lot of mud and water in ‘Wuthering Heights’).

Unpalatable truths and tough nuts to crack

Another skeptical reader may say: “Yes, that’s all very well, but this preface was written AFTER Wuthering Heights was published!”

Very true. But here is what Anne wrote at the very beginning of her first novel ‘Agnes Grey’, which was published together with Wuthering Heights in 1847:

“All true histories contain instruction; though, in some, the treasure may be hard to find, and when found, so trivial in quantity, that the dry, shriveled kernel scarcely compensates for the trouble of cracking the nut.”

So Emily’s beloved sister is adamant that there’s a treasure to be found in ALL true histories, not just her own, and that in SOME of them, this treasure can be found only after ‘cracking the nut’. Ok, Anne is not Emily, granted, but we know they were ‘inseparable’ and that these words were written at around the same time that Wuthering Heights was being written. So is it too much of a stretch to imagine these two sisters sitting together, in their living room overlooking the moors, discussing how to conceal an unpleasant moral in their novels, and perhaps even laughing about it together?

But let's stick to the facts...

Anne also makes it clear that her readers may not like her moral at all, once they find it, but she doesn’t care, cause she’s not writing to please us! She’s only writing sweetly enough to help the medicine go down (in Mary Poppins’ fashion):

“When I feel it my duty to speak an unpalatable truth, with the help of God, I will speak it.”

So, armed with these first clues, I started peeling back the layers, cracking my walnut, diving into the well and searching among mud and water for the unpalatable moral whispered inside Wuthering Heights.

And here’s what I found…

A fairy-tale.

In fact, a fascinating fable.

Aesop’s fable at the root of Wuthering Heights

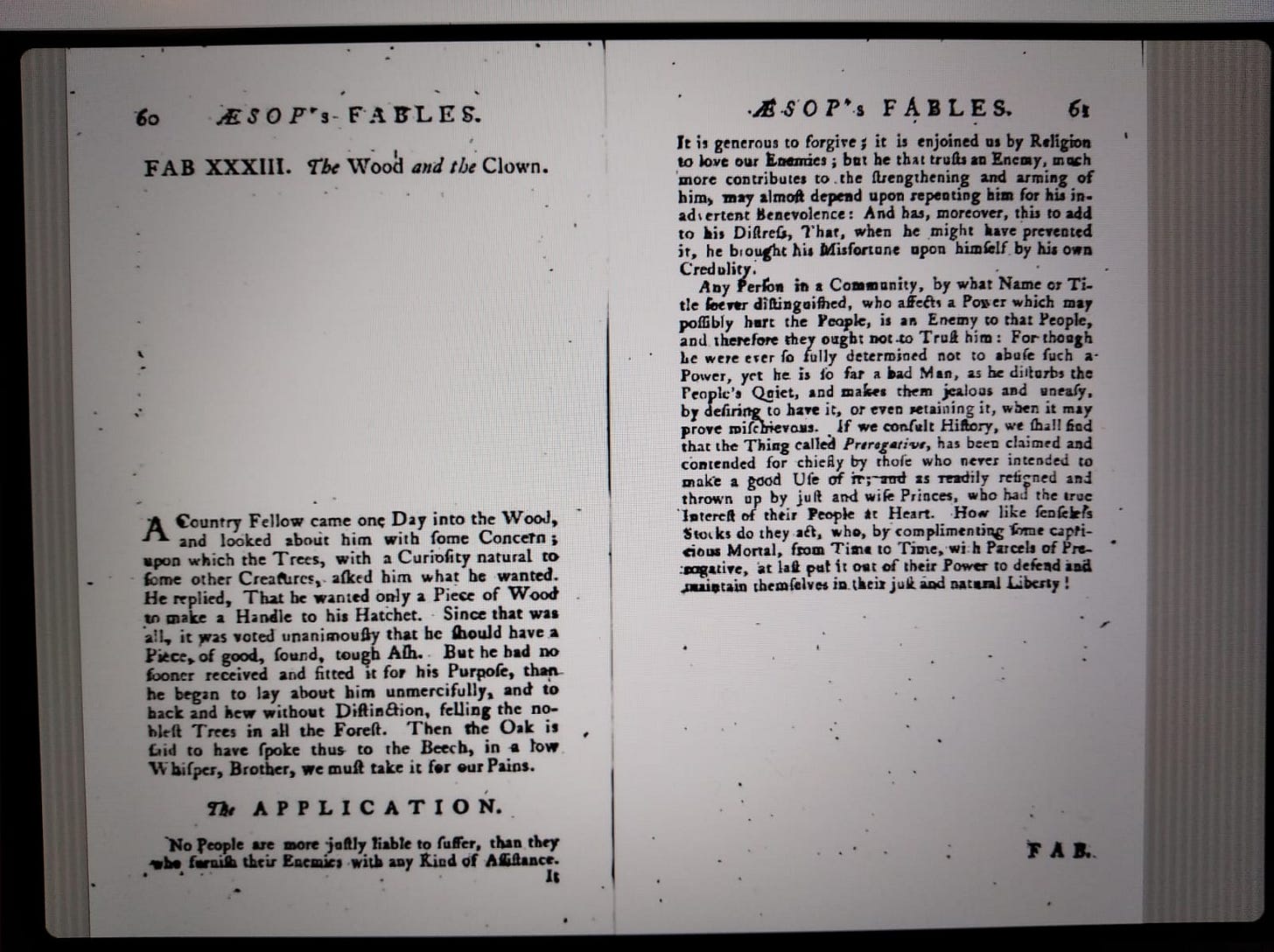

The one that I believe is central to understanding the moral of Wuthering Heights comes from a popular book published in 1788 by Samuel Croxall: “Fables of Aesop and others”. According to the experts, this book was still very popular when the Brontës were little girls. There was an edition published in 1825. Emily was 7 at the time. The perfect time to read Aesop’s fables.

How do we know that Emily read these fables?

Easy.

Because her sister Charlotte herself tells us about it!

You will have heard a million times the story of how the girls started imagining stories starting from some wooden soldiers that their brother Branwell was given by their father, etc. etc. etc. What is less known is that they also started imagining stories starring characters out of Aesop’s Fables. But let me quote it to you straight from Charlotte’s miniscule handwriting, childish spelling included. (I just added some commas for clarity).

In 1829 she wrote what is known as ‘The history of the year’ to explain the origin of the characters they called ‘The O Dears’:

“We pretended we had each a large Island inhabitated by people 6 miles high. The people we took out of Esops fables. Hay Man was my cheif, Man Boaster Branwells, Hunter Annes and Clown Emily’s.”1

So we know for a fact that Emily at some point as a child or as a teenager was fascinated by one particular fable, whose main character was a ‘Clown’. That fable is indeed included in the Croxall’s book with the title ‘The Wood and the Clown’. 2

Now, at this point, all that the Brontë experts seem interested in establishing is which version of the fables was read, what edition and so on and so forth. That’s all very well, but I wonder how many of them actually read those fables, or how many bothered to read them through Emily’s eyes, or to find any connection with her masterpiece. I did, I tried at least, and I may be completely wrong, but here’s what I found…

‘The Wood and the Clown’: Letting evil in ‘of our own accord’

First of all, the ‘Clown’ of this story is not a clown as we think of them today, circus-style, but a clown according to the archaic meaning of it: ‘an unsophisticated country person; a rustic’ (Oxford Dictionary).

So in short, if you’re too lazy to read it yourself, it is the story of a rustic man (the Clown) who goes into a forest to look for a bit of wood to use as a handle for his hatchet, which was broken or something. The trees, who are very curious, very kind and way too generous, let him in and oblige his request by giving him a piece of wood. What harm can it do? The Clown fixes the handle of his hatchet with it, and then starts felling all the trees in the forest! One by one.

The horror! The two trees left standing at the end say to each other, in true Aesop’s fashion: “Brother, we must take it for our pains”.

The moral couldn’t be clearer: “If you LET evil IN, of your own accord, then it’s partly your fault and your responsibility if you suffer.”

Unpalatable uh? I had warned you.

(And I’m not saying I agree either. Don’t shoot the messenger.)

Right after the fable, in the book, we find the ‘Application of the fable’ (which is longer than the fable itself) where Croxall says: “No people are more justly liable to suffer than they who furnish their enemies with any kind of assistance”.

Now that you know the fable, here is how I connected the dots noticing examples of its moral throughout Wuthering Heights.

*** SPOILER ALERT ***

Let’s start with Chapter 27. Nelly and Catherine Linton enter Heathcliff’s house, after being deceived by Linton, only to be locked up in it for days against their will.

What does Heathcliff say to them when they desperately complain saying that what he’s doing is against the law etc.?

“You cannot deny that you entered my house of your own accord.”

Enough said.

And in case readers had missed that sentence, Emily makes sure we take notice.

In the following chapter, Nelly - finally free - goes back to Thrushcross Grange and tells the whole story to Mr. Linton:

“As soon as he recovered, I related our compulsory visit, and detention at the Heights. I said Heathcliff forced me to go in: which was not quite true.”

See? She’s well aware they entered of their own accord!

Or just consider how gladly Isabella Linton ‘lets Heathcliff in’ by running away with him, only to then find herself in a hellish situation of domestic violence. Her own brother Linton reminds Nelly that “she went of her own accord”.

‘Suit yourself now’, basically.

Another striking example is in chapter XIV (and in the following one).

Heathcliff is asking Nelly to help him in his determination to see Cathy one more time, without Mr. Linton finding out about it. He says: “You could do it so easily. I’d warn you when I came, and then you might let me in unobserved, as soon as she was alone.”

And sure enough, the first Sunday her Master goes to Church, Nelly brings Heathcliff’s letter to Cathy and then literally lets him in, by leaving the doorS open (yes, plural): “We generally made a practice of locking the doors during the hours of service; but on that occasion, the weather was so warm and pleasant that I set them wide open […] as I knew who would be coming.”

And of course: ‘The open house was too tempting for Heathcliff to resist walking in’.

(But more on Nelly’s role in helping Heathcliff in another article on her.

Spoiler alert: I’m not a fan).

Unveiling Nelly Dean: when good intentions pave the road to Hell

“The road to hell is paved with good intentions”, declares a very old proverb. Today, whether or not we believe in hell, we tend to use that saying to suggest that despite our well-meaning intentions, our actions can sometimes lead to unforeseen negative outcomes.

Opening latches and ushering evil in

While re-reading Wuthering Heights in light of this fable, I couldn’t help noticing Emily’s constant focus on doors, latches, chains, gates and locks which get opened when they shouldn’t be or are left open when an enemy is around, allowing them to infiltrate.

Let me read you an example from ch. 2.

Mr. Lockwood is telling us about his visit to Wuthering Heights:

“On that bleak hill-top the earth was hard with a black frost, and the air made me shiver through every limb. Being unable to remove the chain, I jumped over, and […] knocked vainly for admittance, till my knuckles tingled, and the dogs howled.

[…] I wouldn’t keep my doors barred in the daytime.

I don’t care. I will get in!

So resolved I grasped the latch and shook it vehemently.”

Ah, Mr. Lockwood…

Or remember the famous scene when Heathcliff comes back after his long absence, in chapter 10?

We are told by Nelly that:

“He leant against the side, and held his fingers on the latch as if intending to open for himself.” And even if he does ‘lift the latch’ himself to enter, it is Nelly eventually who ‘ushers him in’. And then Catherine. And finally Mr. Edgar Linton too gives him “a cordial reception”.

Then we are told by Cathy that he “installed himself in quarters at Wuthering Heights” and pray, who lets him in there too, with open arms?

Hindley! His step-brother Hindley, a man who hated his guts and who Heathcliff in return hated with a vengeance. And yet we are told by Cathy that :

“Hindley came out and fell to questioning him of how he had been living, and finally, desired him to walk in...”

I mean…

What did the trees say in the fable again?

“Brother, we must take it for our pains”

And who is the only character who keeps his doors and gates and room well shut and barred? Heathcliff. He sure knows how to let enemies out.

But there’s more to the Application of Aesop’s fable than reminding us of our own responsibilities in letting evil and enemies in.

The breaking point: when forgiving a seventy-first time is too much

Mr. Croxall goes on to say that we should be careful when forgiving an enemy.

“It IS generous to forgive, it is enjoined us by Religion to love our Enemies, but he that trusts an enemy, much more contributes to the strengthening and arming of him, may almost depend upon repenting him for his inadvertent benevolence.”

And doesn’t ‘Wuthering Heights’ mention ‘forgiveness’ an awful lot?

The other dream Mr. Lockwood has, right before the famous “Let me in” one, is of a preacher stressing the importance of forgiving “seventy times seven”. This is not Emily being melodramatic with numbers. It’s in the Bible itself. Matthew 18. Verses 21-22.

“Lord, how many times shall I forgive my brother or sister who sins against me? Up to seven times?” and Jesus answers: “I tell you, not seven times, but seventy times seven."

But there comes a time, Lockwood tells us through his dream, when forgiving someone is too much and even Jesus wouldn’t condone it. “The first of the seventy first” is the final drop. Lockwood had enough and says so out loud in his dream. And isn’t it imperative we all learn to say our “I had enough!” when the time is right, or before it’s too late?

It is sometimes a life-saving lesson to learn, especially for us women, as Isabella Linton shows us when she finds the courage to leave Heathcliff for good.

She had enough. It is the first of the seventy-first for her! And she has no intention of forgiving him any longer:

“As he was the first to injure, make him the first to implore pardon; and then— why then, Ellen, I might show you some generosity […] But it is utterly impossible I can ever be revenged, and therefore I cannot forgive him” , she says.

Heathcliff, the Wood-cutter and Clown in the Fable (and ‘Rustic all through’)

As soon as I put these first pieces of the puzzle together, I then looked up the word ‘clown’ in Wuthering Heights. And there it was. Four times.

Once in chapter 31, where Mr. Lockwood is describing Catherine Linton:

“Living among clowns and misanthropists, she probably cannot appreciate a better class of people when she meets them.”

“Clowns and misanthropists”. Now, since there are only Heathcliff, Hareton and Joseph in the house, one of them must be the Clown. Heathcliff certainly fits the bill of the violent, cruel one in Aesop’s fable.

In another chapter, Catherine tells us that she would not marry a Clown.

The last times the word Clown appears are related to Hareton though.

But we know that Hareton at this stage has indeed become quite a ‘clown’, in emulation of Heathcliff (‘emulation’, another important keyword, but more about that in another article).

“Hareton stared up, and scratched his head like a true clown” and “The clown at my elbow, who is drinking his tea out of a basin [...] may be her husband”, says Mr. Lockwood, who seems to me to be the character who offers all the keywords which unlock the moral hidden in the novel (and perhaps it’s no coincidence that his name is LOCK - WOOD, but let’s not go too far).

If that was not enough, we have this early description of Heathcliff in chapter 4:

“A rough fellow, rather, Mrs. Dean. Is not that his character?”

“Rough as a saw-edge, and hard as whinstone!”

A SAW-EDGE.

A perfect symbol for a wood-cutter.

And as a reader who I shared this information with noticed, towards the end of the book, when he’s close to dying, speaking about young Hareton and Cathy, Heathcliff says to Nelly:

“I get levers and mattocks to demolish the two houses, and train myself to be capable of working like Hercules, and when everything is ready and in my power, I find the will to lift a slate off either roof has vanished!”

Mattocks! (thank you Helen Fryers for pointing this out)

Funny choice of words, which can’t be explained without the fable framework.

Mattocks are usually needed by gardeners, and soldiers, to break and extract roots from the soil or to remove tree stumps.

Hareton and Catherine, still being young, are easy to…eradicate.

One does not need an axe. But it’s still a job for a Clown /Wood cutter.

One last thing about the word ‘clown’. I used the Oxford Dictionary before, to find its archaic meaning, but that’s not the dictionary Emily perused. So I looked up the word in the very dictionary the Brontës owned (Browne’s ‘The Union Dictionary’), and again the word CLOWN there means: ‘A rustic. A coarse ill-bred man.’

There is no second meaning.

And where had I seen the word RUSTIC before, outside this novel but describing it? You may recollect that when writing about ‘Wuthering Heights’ after Emily’s death, her sister Charlotte wrote: “With regard to the rusticity of Wuthering Heights, I admit the charge, for I feel the quality. It is rustic all through.”

Was she giving us all a big hint?

That mysterious ash-tree…

Finally, to add the last missing peace of the puzzle I asked myself: what type of tree was mentioned in that fable? Perhaps, if my theory holds, I gathered, we should find it mentioned in Wuthering Heights, especially in a strategic scene where readers would be compelled to notice it.

So let me take you back one last time to Aesop’s own words, in the Croxall edition:

“[The clown] replied that he wanted only a piece of wood to make a handle to his hatchet. Since that was all, it was voted unanimously that he should have a piece of good, sound, tough ash.”

An ASH tree. That rang a bell... Where had I seen that word before?

I quickly double checked in my ebook, and there it was.

Chapter 16 of Wuthering Heights. A central chapter in the story. It’s the morning after Catherine’s death. Nelly is venturing out after sunrise to give Heathcliff the terrible news. She finds him “there--at least, a few yards further in the park; leant against an old ash-tree.”

I rest my case.

And if this hint wasn’t enough, I believe that Emily tried at the very beginning of the novel to remind us of this fable, with a powerful image: “Terror made me cruel”, Mr. Lockwood says, speaking of the creature who is crying ‘Let me in!’ in his nightmare, and then he proceeds to pull its wrist on to the broken pane, “and rubbed it to and fro till the blood ran down and soaked the bedclothes”. What is this action literally describing, if not the act of sewing a tree?

(Please spare me the Freudian alternative).

How do we keep evil out? The first remedy

I believe that Emily Brontë did not simply put us on our guard with her story, about the dangers and responsibility of letting evil in ‘of our own accord’, etc.

Since a stitch in time saves nine, I believe she also gave us a remedy, right there in the first chapters.

And it’s not even that symbolic.

After all, as Adam made me notice as we were discussing the book together, Mr. Lockwood in the end did NOT let the ‘creature’ in, in his famous nightmare.

And yet we are told that ‘it maintained a tenacious gripe’ on him, its ‘hand clung’ on his. So how did he manage to set himself free?

Again, we just have to read Mr. Lockwood’s words carefully.

“I snatched (my hand) through the hole […] and stopped my ears to exclude the lamentable prayer”.

There you go. Here’s our first remedy.

When an evil creature has a hold on us (be it an evil person, or substance, or what you will), the minute they finally release their hold for a second, we must be quick, seize the day and stop listening to their constant whining to be admitted in, we have to be like Ulysses with the mermaids.

And speaking of people whining: who is the character in Wuthering Heights whose constant lamentations lead Catherine Linton to fall into a terrible trap?

…

Yes. Heathcliff’s son Linton, to whose pleas to be accompanied to Wuthering Heights in chapter 27, our generous and trusting Catherine gives in, just like the generous, trusting trees of the fable give in to the Clown’s request, to their own demise.

She didn’t have Emily’s advice to save her. But we do.

The best remedy: “a pyramid of books”

And there was a second remedy hidden in that sentence by Mr. Lockwood.

I didn’t give you the full quotation before.

So here it is in full: “I snatched (my hand) through the hole, hurriedly piled the books up in a pyramid against it, and stopped my ears to exclude the lamentable prayer”.

So according to Emily Brontë, “a pyramid of books” is literally the key to breaking free from the clutches of evil.

And this advice perfectly matches the symbolic ending of the novel, where Cathy teaches Hareton how to read and gives him a book as a gift, saving him from becoming a second Clown like Heathcliff.

THE SPINSTER’S TAKEAWAYS

Summing up:

Wuthering Heights is much more than a Gothic novel written for fun.

I believe it is a modern retake of a very ancient, timeless fable, inspired by Aesop, and that the three magic, enigmatic words “Let me in” act as an incantation guiding us to the hidden moral.The fable’s moral teaches us that if we let evil in of our own accord or help our own enemy, then we have ourselves to blame too. An unpalatable moral, but as we saw, when these literary spinsters “feel it their duty to speak an unpalatable truth...they will speak it.”

Emily Brontë gave us some remedies to protect ourselves against this bitter fate: be aware who you let in, don’t forgive too often, don’t lend your ears to whining evil influences and don’t lend an axe to an enemy. (Or at least don’t go crying to Emily, if you do, if you don’t want her to say: “Sister, we must take it for our pains”).

The advice Mr. Lockwood gives us about using a ‘pyramid of books’ to block out evil can still be a life-saving lesson for us today, especially if the wise book gifted to someone in need, and read between the lines, is… Wuthering Heights.

Thank you Emily.

And thank you for reading.

E.V.A.

‘The history of the year’ by Charlotte Brontë

Link: TheBrontes.net

‘Fables of Aesop and others’ by Samuel Croxall (page 60)

Link: Archive.org