Unveiling Nelly Dean: when good intentions pave the road to Hell

“The road to hell is paved with good intentions”, declares a very old proverb.

Today, whether or not we believe in hell, we tend to use that saying to suggest that despite our well-meaning intentions, our actions can sometimes lead to unforeseen negative outcomes.

That’s why we often say: “I’m really sorry, I didn’t mean to…”

But that is not what this proverb meant at the time of the Brontës.

And I believe that Emily Brontë created the character of Nelly Dean, and the plot of Wuthering Heights, to be the perfect exemplification of this proverb’s original meaning, and to give us all a powerful warning.

So, the original meaning of this proverb could be translated today into something like this: “The road to Hell is paved with all the empty, good intentions of people who talk the talk but don’t walk the walk”, of people who are ‘all mouths and no trousers’, who have a lot of good intentions, but don’t actually act upon them, like our Nelly.

Nelly Dean: a ‘worthy woman’ or a villain?

Before we go any further: who is Nelly Dean? And is she a good or evil character?

What do you think so far if you’ve read the book?

Nelly Dean (or Ellen Dean or Mrs. Dean) is the main narrator of the novel, so we see all the characters through her eyes, except for Mr. Lockwood, the second narrator. And she’s such a great story-teller (cause let’s face it, she’s amazing) that when we read the novel for the first time (and most people will read it just once or twice, unlike nerds like me!), we get so caught up in her juicy narration and in the story of Heathcliff and Cathy, that we don’t really pay much attention to Nelly herself, and to what she says, and most of all we don’t really mark whether or not she actually does what she says she will do.

(Spoiler alert: she doesn’t!)

She’s just there in the background, sitting on her chair with her sewing basket, chatting away to keep Mr. Lockwood company or cooking her Christmas cakes and scrubbing the floor, so we don’t question whether or not she stands for something, symbolically.

And yet she’s in almost every scene, all the time, from the get-go, so clearly Emily Brontë must have paid a lot of attention to the writing of this character. Now, most readers tend to think of Nelly as a “worthy woman”, because that is precisely as both Mr. Lockwood and Heathcliff describe her. We tend to see her as a good, old, sensible servant, who is kind, compassionate, faithful to her masters and maternal (after all she raises little Cathy and little Hareton). Granted, she’s curious and a bit of a gossip too, but we kind of like that, don’t we? Because that way we get to know all the dirty details of all the characters, so we readily excuse all that spying.

Only a minority of readers don’t like Nelly, and even fewer think she’s a proper villain, and it has to be said, Nelly certainly does some petty, nasty things in the book, and says some pretty mean, cruel words here and there. So at the very least she is petty, and wicked, but is she really a villain?

I believe that this is taking things too far.

She has no reason to be evil, no motive, and she doesn’t willingly plot to harm anyone.

Plus Emily Brontë makes it super clear that Heathcliff is the utmost expression of evil. I mean, it doesn’t get more evil than (spoiler alert) to let your own son die, marry a woman only to abuse her, and lock your niece up so that she will miss being with her dying father.

If that isn’t Satan incarnate, I don’t know what is.

But evil people are not the only ones on the road to Hell, as the saying goes.

People with good intentions are also there keeping them company.

So let’s go back to that proverb now and to its links with Emily Brontë.

Being a good, worthy person is not enough

First of all, who made this saying popular in England and when?

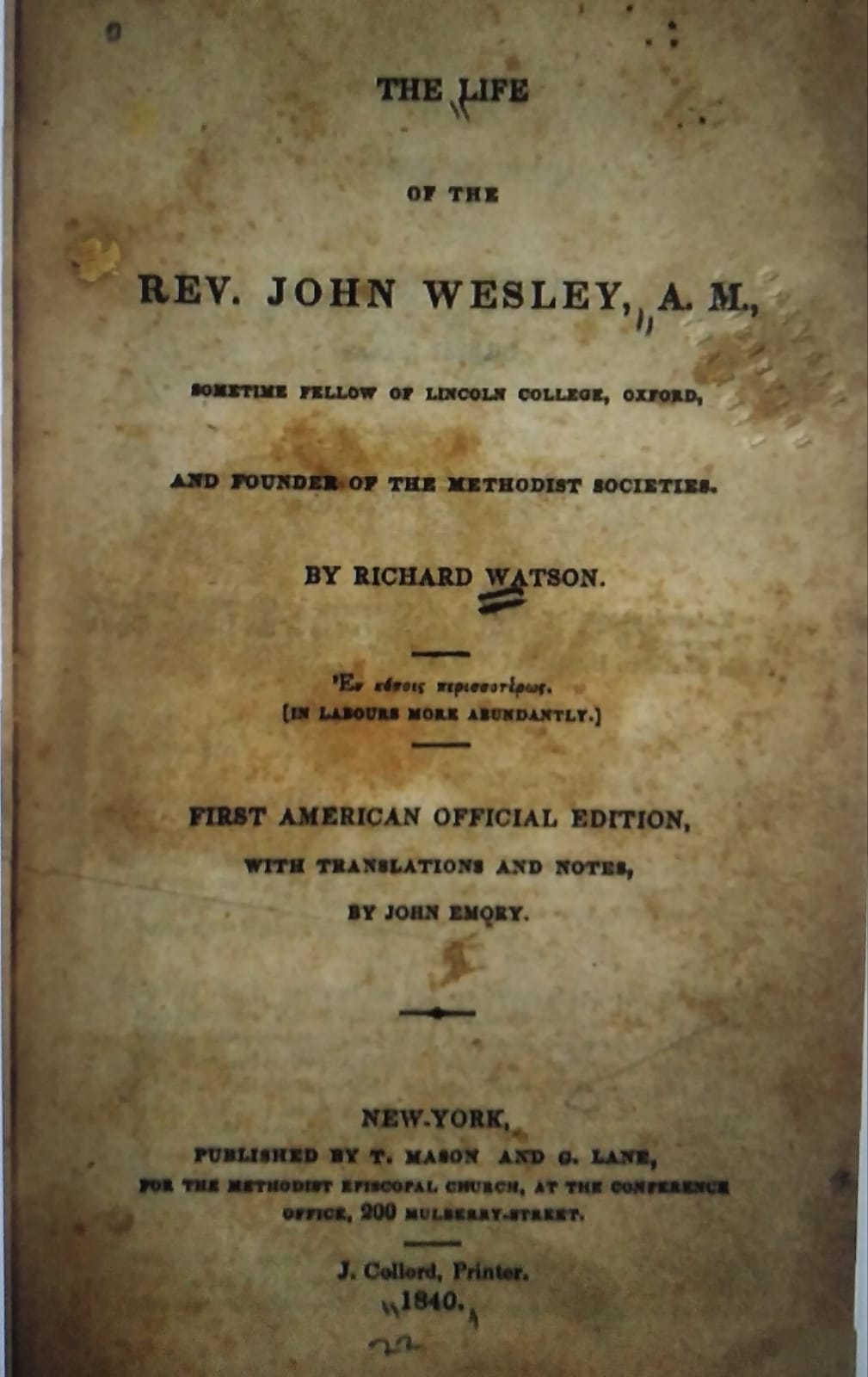

It was an 18th century English Methodist preacher called John Wesley.

The saying appeared in one of his most famous sermons, titled ‘The almost Christian’.1

It is quite a long and boring, but don’t worry: I’ve read it all so you don’t have to, and most importantly, I have tried to read it through Emily’s eyes.

But you may want to know: how did I know that Emily knew Wesley and this proverb?

I didn’t. I had no idea at first. So when one day it hit me that this saying perfectly described Nelly, I just hoped to find some connection with the Brontës. So imagine my surprise when I found out that that Emily’s own father was a follower of this preacher and was even acquainted with the wife of Wesley’s best friend.

And on the mother’s side, back in Cornwall, they even had Wesley stay at some relatives’ , when he was touring Cornwall on his preaching tour2. If that wasn’t enough, I discovered that Emily’s parents met at a school called Woodhouse Grove, whose first original name was ‘The Wesleyan Academy’. And finally, the family very likely owned a biography of the worthy Reverend.

As for the proverb itself (‘The road to Hell is paved with good intentions!’) I couldn’t be sure that Emily knew it of course, but then I found out that her sister Charlotte certainly did. In ‘Jane Eyre’, Chapter XIV, Mr. Rochester says: “I am paving hell with energy […] I am laying down good intentions, which I believe durable as flint.”

I almost fainted when I saw that. Bingo.

So what is this sermon all about? And what does it have to do with Nelly Dean?

And why is it important for us readers, even today?

The title already says it all: ‘The almost Christian’.

So basically Reverend Wesley believed that too many people at the time thought of themselves as good Christians - or good citizens we may say today - only because they went about their daily life trying to live in peace with all men, performing ‘little office of humanity […] without any expense or labour’, and giving others assistance if it was ‘without prejudice to themselves’ etc. Nelly Dean exemplifies all these qualities. She’s not evil, but she never really goes out of her way to do good. And Wesley clearly says that this is not enough to make a proper, true Christian. You cannot just have good intentions, you have to act upon them.

And I believe that Emily believed that too and tried to warn us.

In fact, it is Nelly herself who ironically declares this central concept. In chapter VIII of the second volume, little Cathy says: “I love (my father) better than myself”, and Nelly replies: “Good words but deeds must prove it also.”

But really, I wouldn’t even need to quote Wesley to prove the influence of this concept. All the Brontës knew the Bible very well and in James 2:14-17 we are told: “What good is it, my brothers and sisters, if someone claims to have faith but has no deeds? Can such faith save them? … Faith by itself, if it is not accompanied by action, is dead."

But before I move on to show you more examples from ‘Wuthering Heights’, there is a second proverb I believe Emily used as a road-map to create Nelly, and as an inspiration for the moral behind ‘Wuthering Heights’, a proverb which is even more powerful and more relevant for modern readers who aren’t afraid of going to Hell.

The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is… a Nelly Dean

One night, as I was listening to ‘Wuthering Heights’ as an audiobook for the umpteenth time, towards the end of the novel I heard Nelly say this:

‘I seated myself in a chair; and rocked to and fro, passing harsh judgment on my many derelictions of duty; from which, it struck me then, all the misfortunes of my employers sprang.

It was not the case, in reality, I am aware; but it was, in my imagination, that dismal night’

That night I finally realised that she was actually telling us the truth, and that all the misfortunes of the main characters did indeed spring from Nelly’s many ‘derelictions of duty’. And that’s when this famous proverb just came up to me out of the blue:

'The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.’

And again I had to immediately double check to make sure that Emily Brontë knew it.

So who made this proverb famous?

Apparently it was Mr. Edmund Burke, an 18th Century Irish philosopher.

What he actually said are not those exact words but something much more articulated.

The concept at the base of that saying is found towards the end of a 1770 book called: ‘Thoughts on the cause of the present discontent’. 3

Again, I’ve read it so you don’t have to, and once again I’ve tried to read it through Emily’s eyes and, lo and behold, tell me if this is not a description of Nelly Dean, almost word by word:

“It is not enough that a man means well […] It is not enough that in his single person he never did an evil act […] and even harangued against any design which he apprehended to be prejudicial to the interests of his country […] This innoxious and ineffectual character that seems formed upon a plan of apology and disculpation falls miserable short of the mark of public duty. That duty demands and requires that what is right should not only be made known, but made prevalent, that what is evil should not only be detected but defeated.”

So, what matters now is to know whether or not Emily knew Edmund Burke.

Otherwise it’s just all a lot of interesting speculations.

But the link between this philosopher and the Brontë family is no speculation at all. It turns out that they owned a book by Edmund Burke himself: ‘A philosophical inquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and the beautiful’ - An 1827 edition4.

So now that you know these two proverbs, and know the connection with the family, it is time to put my theory to the test: if I’m right and Emily used these very proverbs to create the character of Nelly Dean, and through her the plot and moral hidden in ‘Wuthering Heights’, then all her words and actions in the novel should make complete sense within this framework.

But before I give you examples of Nelly’s many ‘derelictions of duty’ in Wuthering Heights, if you haven’t read my previous article, then maybe now it’s a good time to pause and go read it, or listen to it, because that’s where I laid the foundations of the unpalatable moral hidden inside the book and the code that cracks it: a fable by Aesop.

“LET ME IN!” - The password to Wuthering Heights

“Let me in!” are three of the most haunting words in English literature. Even someone who has never opened a book since secondary school will recognise them. There are nine words actually, not three, because this famous cry is repeated three times in the third chapter of Wuthering Heights:

Let’s go spy on Nelly

Ok. Time to go spy on Nelly now. She has been openly spying on a lot of characters herself, so it’s time to get even. I will write only a few examples here and give you plenty more in the read-along (or ‘Lullaby for the soul’ as I call it).

I will start from the chapters where she reveals her good intentions, but doesn’t carry them through, so where she’s a specimen of Wesley’s first proverb: “The road to Hell is paved with good intentions”.

(Spoiler alert)

Let’s start from chapter XI. Nelly is thinking of her foster brother Hindley, who is on the road to perdition, drinking and losing money playing cards with Heathcliff, and Nelly says:

“I’ve persuaded my conscience that it was a duty to warn (Hindley) how people talked regarding his ways and then, hopeless of benefiting, have flinched from re-entering the old house.”

Ah. So close Nelly!

Then, when she finally musters the courage to go ‘up at the Heights’ to check up on him, she says: “instead of Hindley, Heathcliff appeared on the door stones and I turned directly and ran down as hard as ever I could race.”

Ah. So brave. Such an inspiration, isn’t she?

And think of the terrible scene where she is finally set free by Zillah, after being forced to remain for days at Wuthering Heights. When she goes looking for Cathy - who is still locked up somewhere - she only finds Linton seated in a room and there she threatens him like a bull:

“Direct me to her room immediately, or I’ll make you sing out sharply!”

Well, does she make him sing sharply?

Of course not.

And remember, we are not talking something minor here.

We are talking life and death situations, where Nelly’s prompt actions and courage could have spared Cathy physical abuse, possibly even sexual abuse and certainly a lot of trauma.

But let’s see now where Nelly is the exemplification of the second famous proverb:

“The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing.”

In chapter XII, Mr. Kenneth, the Doctor, sees Nelly on the road and warns her about Isabella wishing to run away with Heathcliff and tells her: “You urge Mr. Linton to look sharp!”

Does Nelly warn her master?

Nope!

And even after discovering that Isabella’s room is already empty, she figures that it would be too late to run after her anyway, so why bother?

“I dare not rouse the family, and fill the place with confusion, still less unfold the business to my master… I saw nothing for it but to hold my tongue and suffer matters to take their course.”

And finally, in chapter XXVI, Nelly tells us that Mr. Linton is convinced that his nephew - Linton - must be a good boy, since he ‘resembled him in person’. Nelly knows a thing or two about the treacherous boy, but does he warn her master about the danger he represents for Cathy, if they married? Of course not!

“I, through pardonable weakness, refrained from correcting the error; asking myself what good there would be in disturbing his last moments with information that he had neither power nor opportunity to turn to account.”

And mind you, Emily herself uses that verb (to triumph) in connection with Heathcliff, when she has Mr. Linton say, before dying: “I’d not care that Heathcliff gained his ends, and TRIUMPHED in robbing me of my last blessing.”

Now let me rephrase the proverb so it’s clearer: “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for a Nelly Dean to do nothing.”

And when have you been a Nelly Dean recently?

…

See? It gets interesting when we realise how still relevant this message is today.

‘Pardonable weakness’?

What I believe makes us readily excuse Nelly, when we first read the novel, and overlook her part in letting evil win, is her apparent compassion. Let’s take a look at this example, which I can imagine took Emily a long time to create so perfectly.

In chapter VII of the second volume, one day little Cathy meets her cousin Linton by chance while walking on the moors. Heathcliff is there with the child and he’s not ashamed to tell Nelly his evil plan. He wants to marry Cathy to Linton.

Nelly looks shocked and horrified and says: “I am resolved she shall never approach your house with me again”

Skip to the next chapter and what are we told?

“Next day beheld me on the road to Wuthering Heights, by the side of my wilful young mistress’s pony.”

Enough said!

Once they are both locked in the house, Heathcliff even slaps Cathy ferociously.

Does Mrs. Dean intervene to protect her?

No, she doesn’t. And how does she disculpate herself? She says:

“Heathcliff glanced at me a glance that kept me from interfering.”

So a glance is all it takes to stop her, or a “touch on the chest”!

Let’s hear again what Edmund Burke wrote, about people who do nothing to stop evil: “This … ineffectual character … seems formed upon a plan of apology and disculpation”.

Exactly.

Which leads me to a word which I noticed was repeated a bit too often, when Nelly was talking: “poor”. She seems to find everyone “poor”:

“I nursed her, poor thing”

“The poor fatherless child”

“Poor soul!”

I checked in my ebook and she says it 32 times!

A bit too often not to be a secret clue from Emily to her readers, I believe.

So we cannot say that Nelly is an evil character, but she’s definitely quite a hypocrite, and definitely not a true Christian, and her lack of actions cost other people’s life or their health or their sanity.

And Emily clearly did not tolerate hypocrisy. If evil is around, it has to be stopped. Saying “poor thing”, “poor creature” means absolutely nothing.

And the irony is that Nelly tells us herself the danger of this fake compassion.

“There’s harm in being too soft,” she says once.

So having good intentions but not acting upon them is not much better than not having any good intentions at all.

Which leaves me to the last batch of examples from the novel, where Nelly even actively lets evil in, literally, opening doors to Heathcliff.

Remember? In Ch. XIV Heathcliff is desperate to see Cathy one more time and he tells Nelly: “I must exact a promise from you, that you’ll get me an interview with (Cathy) – consent or refuse, I WILL see her!… You could do it so easily! I’d warn you when I came and then you might let me in unobserved…. You would be hindering mischief.”

What does she reply?

“You must not – you never shall through my means. I protested against playing that treacherous part.”

But what does she actually do?

“I argued and complained and flatly refused him 50 times, but in the long run he forced me to an agreement. Was it right or wrong? I fear it was wrong”

And so it happens that three days later she “sets the doors wide open” and lets Heathcliff in.

To quote Edmund Burke one more time: “He trespasses against his duty who sleeps upon his watch, as well as he that goes over to the enemy.”5

Nelly: the hidden enemy

It’s only Catherine, in her delirium, who sees Nelly through:

“Nelly has played traitor, Nelly is my hidden enemy. You witch!”

The only other character who is never fooled by Nelly is Heathcliff, which is probably why, when Heathcliff dies, she cannot manage to close his eyelids. She could never blind him. He knows that she is moved mainly by ‘idle curiosity’, an emotion that Edmund Burke himself, in the book owned by the Brontës, describes as ‘the first and the simplest emotion’. Heathcliff also says he wants ‘none of her prying’ in his house and tells her: ‘I like you, but I don’t like your double dealings’.

Heathcliff is also the only character who always carries out his intentions, good or bad.

Nelly herself notices this trait when Heathcliff is a child. After he has just been ‘knocked down’ by Hindley, he still proceeds to doing what he decided to do before beign beaten.

‘I was surprised to witness how coolly the child gathered himself up, and went on with his intention’, Nelly says. Big hint there again.

And all throughout the novel, Heathcliff’s bad intentions and threats always turn into evil deeds.

His determination has no equal. If only good people had the determination of evil people, the world would be a better place, Emily seems to tell us.

A specimen of true benevolence

The only problem I had with seeing Nelly as an exemplification of those two famous proverbs was Charlotte Bronte's description of Nelly as ‘a specimen of true benevolence’.6 If Charlotte tells us that her sister Emily meant Nelly to be an exemplification of ‘true benevolence’, who am I to disagree?

However, the word benevolence, in its Latin etymology of ‘benevolentia’, simply means having the goodwill to do good. That’s all. So Charlotte is right: Nelly certainly shows true benevolence, but she stops there. She does not act upon it, so it is correct to say that she is the exemplification of ‘true benevolence’.

And the story – just like those two proverbs - makes it clear that benevolence alone is not good enough.

If we re-read ‘Wuthering Heights’ in light of both the Aesop’s fable of my previous article and these two powerful proverbs, we can almost hear Emily Bronte's powerful voice urging us to be braver, to put our good intentions to good use, to stand up against evil and protect the weak, albeit without becoming martyrs.

And I believe she gave us a practical example of how to be a heroine in the character of little Cathy, but more about her in my next article.

For today I will leave you with these quote from Nelly to Mr. Lockwood:

“You’ll judge as well as I can all these things; at least, you’ll think you will, and that’s the same.”

THE SPINSTER’S TAKEAWAYS

Summing up:

Emily Brontë's character Nelly Dean in 'Wuthering Heights' seem to perfectly exemplify the original meaning of two famous proverbs:

1. ‘The road to hell is paved with good intentions’

2. “The only thing necessary for the triumph of evil is for good men to do nothing."

Nelly is portrayed as a character with good intentions but who often fails to act upon them, leading to negative outcomes for other characters.Nelly Dean is mainly seen as a "worthy woman" and not a villain. While showing qualities like compassion and benevolence, her actions or lack of action contribute to the spreading of evil and cause real damage to others.

Emily Brontë - in her creation of Nelly - might have been influenced by the sermons of John Wesley, an 18th-century English Methodist preacher, and by the ideas of Edmund Burke, an Irish philosopher. Both figures discussed the importance of translating good intentions into actions and were both known by the Brontës.

We may reflect on times we may have been like Nelly Dean, having good intentions but failing to act when the situation demanded it. We can read Emily Brontë's masterpiece to find inspiration to be braver and take action against evil.

Thank you for reading.

(And don’t be a Nelly Dean!)

E.V.A.

Reverend John Wesley - Sermon: ‘The almost Christian’ 1872

‘The mother of the Brontës’ - by Sharon Wright

Burke Edmund - Thoughts on the cause of the present discontent - 1770

Burke Edmund - A philosophical inquiry into the origin of our ideas of the sublime and the beautiful - 1827 ed. (Bronte Parsonage Museum - Ref: bb106 )

Burke Edmund - Thoughts on the cause of the present Discontent - II. 86 - 1770

Preface by Charlotte Brontë to ‘Wuthering Heights’ -1850 edition